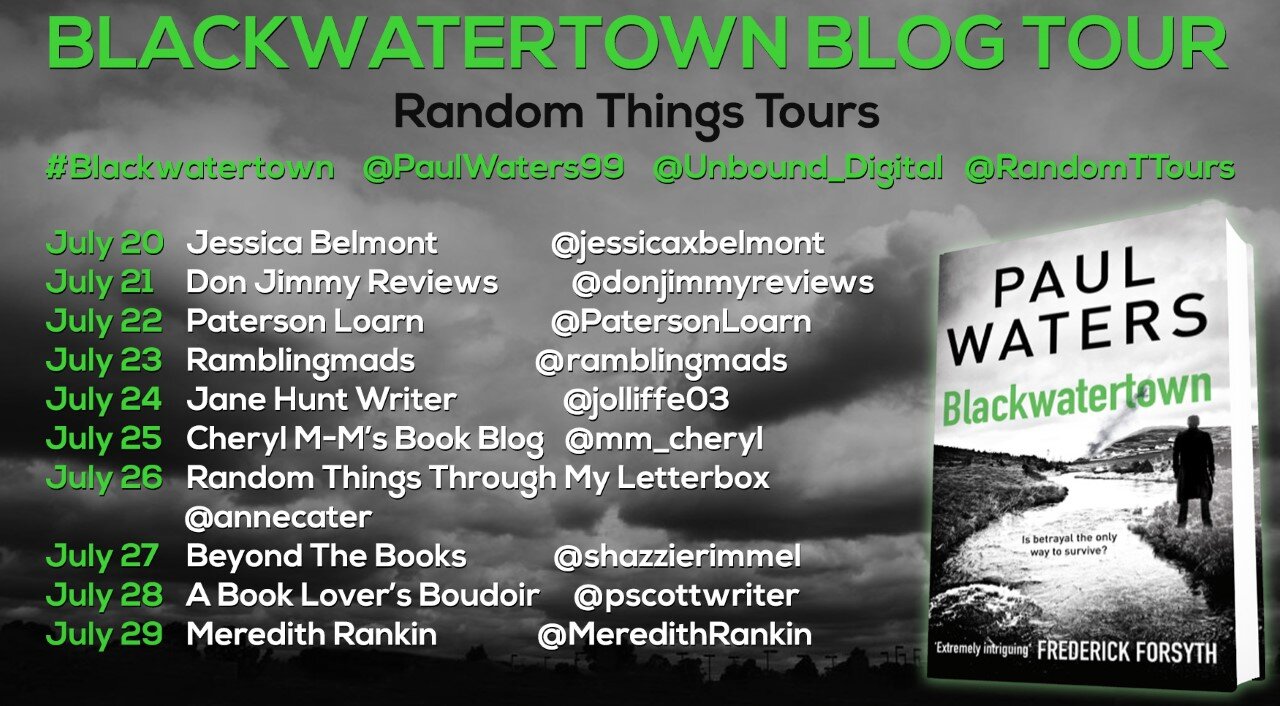

Blackwatertown by Paul Waters

/If you like quirky crime novels, you’ll love Blackwatertown. I relished every page, because I was born in Northern Ireland, where my ancestors were farmers and police officers, and my grandfather marched with the Orange Order. Rural Ulster communities, like the 1950s townland sensitively described by Paul Waters, are part of my family history. When I read the account of Catholic Constable Macken’s enforced attendance at a social event in the Orange Hall, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. I had many questions for Paul, and I’m delighted to present his thoughtful answers.

Paul, in Blackwatertown, you describe dark and terrible events in a style rich in romance and bursting with ‘craic’. Did you set out to do this, or did your characters take over?

People have dark and terrible thoughts and experiences. But real life is also full of lightness, humour and kindness. I wanted to reflect all of it. I enjoy how Sicilian writer Andrea Camilleri switches between farce and darkness, and fancied deploying a bit of that myself. However, as the story developed and I got to know the characters better, they also seemed to bring their own banter and yearning.

When I was a journalist in Northern Ireland, I found that people who had inflicted appalling harm on others could also be disarmingly funny and good company. There was always the risk of being seduced into overlooking their past. Another lesson was that people are multi-dimensional – though their better or worse natures may only be revealed over time, or in extreme circumstances. People in general, and characters in Blackwatertown, are not always how they originally seem!

When you researched historical details for Blackwatertown, which sources did you use?

I wasn’t around in the 1950s. My sources were the oral histories of family members who served in the police on both sides of the Irish border back then, and other tales of relations involved in political violence on one side or another. That’s where you hear the unvarnished visceral truths, about rules bent and broken, lines crossed – who the real killers were and what were the motives.

Although Blackwatertown is a work of fiction, I didn’t want to caricature characters who might also be seen as representing one side of the community or the other – especially as some of the characters in Blackwatertown say and do pretty extreme things. I was keen to remain faithful to the spirit of the times. I researched historical references, books and newspapers, and found the book Portavo – An Irish Townland and its Peoples by Peter Carr, a particularly good reference. I would also recommend Seamus Heaney’s poem Bye-Child. But don’t read it until after you’ve read Blackwatertown.

What is the significance of country sports like fishing and shooting in Blackwatertown?

When you hear stories of war, terror, betrayal and prejudice, you might wonder how anyone ever managed to endure life in Northern Ireland. But it’s also a beautiful outdoorsy place, with space in the mountains and forests and fields to breathe and stretch. Fishing is one of those solitary pastimes that allows you to think things through or switch off entirely. And there’s good fishing in Ireland. Some of the policemen I knew were great big blokes who gave no hint of subtlety, except when teasing out the truth during an interrogation or tickling out a fish from river reeds. As for the shooting, in Blackwatertown the targets are nearly all human. Not very sporting at all.

How important is food as a motif in Blackwatertown?

When I think of Northern Ireland, it’s the food that makes me smile. My first stop on visits home, if it’s a Friday, Saturday or Sunday, is St George’s Market in Belfast. That’s the place for fresh soda, wheaten and potato bread. There are great buns there too. We love our buns and cakes.

If the Orange Order switched from marching to making Fifteens, the world would be a better, happier and fatter place. (To the uninitiated, Fifteens are a kind of traybake that you don’t bake, with digestive biscuits, marshmallow, glace cherries, coconut and other sorts of goodness inside.) All along the north Antrim coast from the Carrick-A-Rede rope bridge to Ballycastle, you’ll find epic and generous cakes. Though I once encountered some truly huge French Fancies at Glenveagh Castle in Donegal. They were immense.

Characters in noir literature typically turn to alcohol as a refuge, but in real life it’s often food. And when there are fresh fish to be caught, wonderful bread to be eaten and giant confectionery – well, nobody can be angry all the time.

Of social interaction during the Fifties, you suggest that ‘In Ulster….a smile may be seen as weak, devious or ridiculing.’ Has anything changed since then?

That’s a difficult question. People’s experiences vary. When I was young, life seemed to be one confrontation or potential confrontation after another. Walking along the street, crossing sectarian boundaries, going through checkpoints and searches, even just going to school – they were a series of subtle assessments and placements by anyone you met. Or it might not be subtle at all. Where are you from? What school do you go to? Are you a Protestant or a Catholic? I had a kicking for being both before I even knew which I was.

There was strong pressure to conform – either to authority or to whatever was the community norm. Difference was not seen as refreshing, but as a challenge. Quirkiness an invitation to a punch in the face. Standing out was risky. I remember being warned about a woman who wore a bright red coat in a drab neighbourhood. It was suspicious, a sign that something was off with her. Her body was discovered after she was shot dead, dumped and branded an informer by the IRA.

Life has clearly improved. Negotiation is still a dirty word for some, but we’ve been through years of political negotiation to get to the current better situation. We had the political double act of former loyalist firebrand Ian Paisley and IRA leader Martin McGuinness, “the chuckle brothers”, smiling along together as First and Deputy First Ministers of Northern Ireland. So progress is possible, if slow. And there’s a growing proportion of the population who prioritise getting along with each other over Orange v Green. Brexit seems to have set things back considerably, but there are still good grounds for optimism.

‘It was only when he encountered prejudice that he felt he was any kind of a Catholic.’ Can you expand on this?’

Some people are enthusiastic worshippers. Others are religious in name only – at least when it comes to organised religion. It’s why churches that are packed on Christmas Eve, have tumbleweed rolling through for the rest of the year. Northern Ireland is notoriously keener than most places when it comes to turning up on a Sunday.

I used to go to Windsor Park football ground as a teenager to watch Northern Ireland. Seeing us beat West Germany 1-0 was amazing. But I was always acutely aware of my Catholic background as I stood in the Kop end. That’s because the anti-Catholic banter, paramilitary banners, songs and official connivance at the sectarian atmosphere, were a constant reminder that I was in hostile territory. I eventually stopped going. I didn’t want to be found out and get my head kicked in. And perhaps I grew less willing to make the compromises required to fit in.

The religion your parents chose for you may not feature much in your day-to-day life - unless someone insults it, threatens you for it or burns or bombs your church. Then standing up for it is more like standing up for your dignity, or standing up against a bully.

I was brought up at home in an atmosphere of religious toleration, ecumenism and curiosity. My regular church-going years are now far behind me, but I would and have, returned to support the right of others to worship in peace, free from threats or intimidation.

The vehicles in the story often malfunction. It reminded me of an old Percy French song, ‘Are you right there Michael?’ (It’s on Spotify!) Is the internal combustion engine a natural source of humour?

The motor malfunctions in Blackwatertown are usually the fault of bullets or bad driving. My father would say that pushing cars in the rain was character building. My character must have a firm foundation, because we sure did a lot of car pushing when I was young. But I’ll trump your Percy French song with O’Rafferty’s Motor Car by Tommie Connor. Val Doonican sang it. “Now two of the wheels are triangular and the third one's off a pram / The fourth is the last remaining wheel from off a Dublin tram.”

I enjoyed the way you throw phrases that are pure NI into the dialogue, without getting bogged down with dialect. I especially liked, ‘They’d not hit a heifer if they were up its arse!’ Did you have a plan about how to use local expressions?

I like local turns of phrase. They’re funny. They add authenticity. They give an insight into what characters think is important. They’re part of the landscape.

The challenge for an author is to include them in a way that runs naturally for readers who already know them, but is comprehensible to readers encountering them for the first time. I didn’t want to add footnotes or interrupt the flow to explain them. I hope the way I’ve woven them through the story works. You, the reader, can judge.